Artist statement

My work is fundamentally concerned with where the truth lies, what truth is and why we do not try to better understand and be more tolerant of each other’s perspectives.

I have always been interested in historical places that remain in everyday use today, such as the Medieval castle in Durham which now provides university accommodation. We pass by these places, not thinking about how much information is hidden in them, often we prefer to believe the myths we are told about the past, instead of investigating the true story. However, even if we do investigate the true story this is still mediated by the teller, it still has a viewpoint attached to it. This concept equally applies to people, there is so much that is hidden inside that we cannot see and even if we can, it is not truly possible to understand the story as experienced by the specific individual, presupposing that they understand it themselves (Figure 1). This was brought home to me a few years ago when I discovered, by accident, that I am adopted. I was shocked, but it helped explain the origin of some of the incomprehensible images I experience from my subconscious and illustrated how little of my “truth” I really understand (Figures 2 and 3).

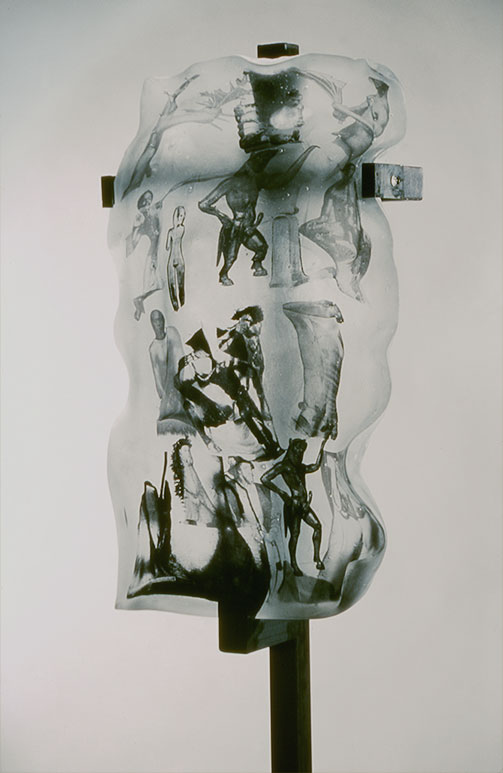

Figure 2.

Self-portrait I and II, 2016

Inclusion of nickel, lead and tin alloy,

hot poured glass into a mould.

Photographed by David Williams.

Searching out the truth, trying to understand it more, is a process of research, problem solving and deep consideration. This is echoed in my exploration of what is technically possible using glass, particularly the scientific processes required to successfully use inclusions of different materials.

Figure 3.

Self-Psychoanalysis V, 2018

Variety of inclusions in glass: water jet cut nickel, tin and lead sheet, gallium and silkscreen printing.

Photographed by David Williams

Even self-analysis of our own behaviour does not allow us to access our deepest thoughts and feelings. We may be scared to access the truth, hiding it deep within our subconscious, until it is lost and inaccessible. However, these hidden fears and emotions can still sometimes seep into our public appearance. This is reflected in Self Psychoanalysis V by allowing the images applied as inclusions to flow from the inside out resulting in damage to the surface of the face.

Where does the truth lie?

To explore this subject fully in my work I needed to discover, consider and utilise an additional space.1 Usually space is invisible until it is occupied, but in traditional opaque sculpture the object often masks the internal space. By using glass, a transparent or semi-transparent medium (Figures 3, 4 & 5), it is possible to make this internal space visible and allow forms to be created within this space. Using both the outer shell and the internal space allows me to explore the theme of where “truth” lies which so demands my attention. I use inclusions within the sculpture to explore the internal space: I continually experiment with different forms of inclusion, be these images or different materials, in order to be able to communicate my message (Figures 2, 3, 5, 6 & 7).

The concept of understanding where the “truth” lies has further developed in my work over time. I have become fascinated by the different interpretations applied to the same “fact” or object when viewed by different people, at different times, in different places or in different contexts (Figure 6). This has become more and more pertinent in a society where the expert is denigrated and the populist is believed. People become ever more entrenched in their own limited perspective and are not prepared to look from other viewpoints, find other ways to see or understand. We look for differences and reject a tolerance of that which is different.

We want to feel young and beautiful, but this is not always possible as by definition we age and standards of beauty change across time and culture. To reflect this I have used a Western contemporary definition of a beautiful body to form a vase which holds various interpretations of the body as it has changed throughout the history of mankind

Figure 6.

Different perspectives, 2016

Kiln cast glass with metal inclusions.

Photographed by Jo Howell

Different perspective employs the perspective techniques used in 2-dimensional work to make it appear 3 dimensional to, inherently 3-dimensional, sculpture. This means that the proportions of the figure vary depending on your view point.

As the sculpture moves from the legs upwards the characteristics of the body parts change from being those of a child through those of an adult as they age. This references that as we age, we also change our perspective.

The Body

I have explored where “truth” lies in two major themes within my work: the body and the cross. Many of my explorations of the body are concerned with the discrepancy between how we view the body and nudity in cultural contexts and how we view them in the real world. In classical and prehistoric art contexts nude bodies are seen as entirely acceptable whereas in real life we do not talk about nakedness, find it uncomfortable, rude or even taboo . In classical art contexts bodies tend to be stereotypically beautiful but in real life that is not how bodies are, even before considering how the interpretation of beauty changes over time and between cultures (Figures 5 & 7).

Figure 7.

Newspaper, 2003

Kiln cast glass with a 3D collage

of the screen-printed inclusions.

Photographed by Tim Adams

Glass was slumped over a mould in the shape of a crucified naked man (life size) with the addition of inclusions of photographs of naked bodies officially displayed in public galleries and museums around the world. Newspaper draws our attention to the reality of a naked Jesus on the cross (which is how he was represented until approximately the 5th Century) and our contemporary discomfort with nudity and sex.

The Cross

Religious symbols are significant for adherents to the religion, but are also often divisive as they are representational of it. I have explored this phenomenon through the cross which was in use in ancient civilisations long before being appropriated by Christianity. In ancient Egypt a cross sign, or Ankh, was the sign of life or the living; the Greek goddess Diana is often depicted with a cross above her head; and, there is evidence of crosses being used in a symbolic manner as far back as the Bronze age. We can also see the cross used across many geographies such as in South America before the Spanish conquest, Europe and Asia. It is also ubiquitous in other religions, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Greek and Roman polytheism and even in the Islamic Maliki sect of the Tuareg. Across many of these contexts the cross was and is a sign of hope, life and fertility. Indeed, we see this in the modern era where biologists use either the arrow cross or the latin cross upon a circle to indicate the male or female gender. However, over time it became weaponised, a symbol of a specific truth. I explore whether it is possible to create a universal cross, a cross that is a sign of hope across different cultures, people and places, to make it something universally beautiful (Figures 8 and 9).

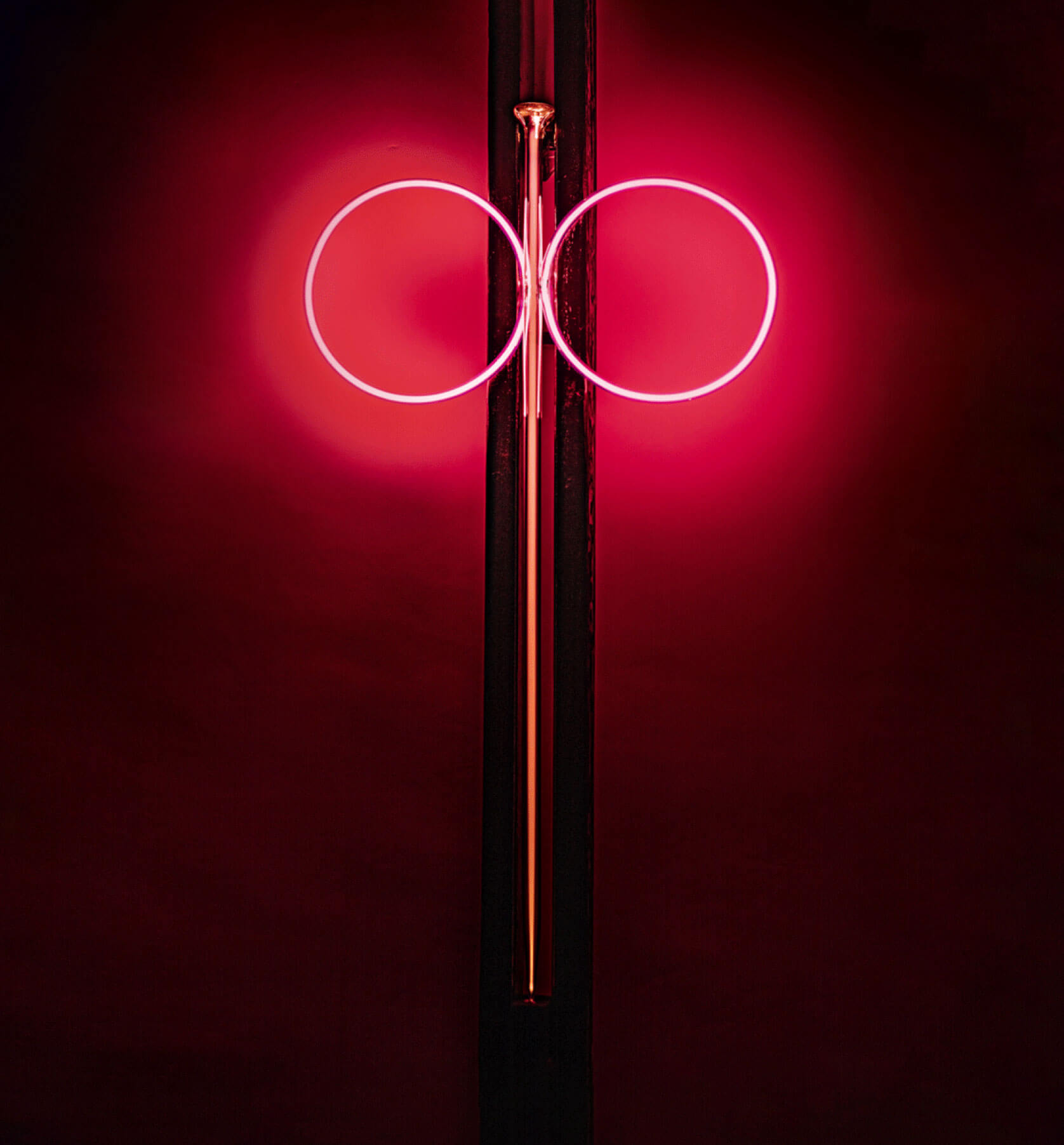

Figure 8.

Peaceful relict, 2020

Neon, recycled wood from

Durham Castle.

Photographed by Voyt Zyzny

Designed to be interactive this aims to help people understand that they do have feelings and that these are valid. However, everyone’s feelings should be taken into account, but on one condition: that they do not harm others.

I tell people it reacts to their negative thoughts. I have noticed that most feel uneasy touching my cross.

Figure 9.

Peaceful relict (talisman), 2004

Necklace; lampworking

borosilicate glass, 24 carat gold

Photographed by David Williams

Jewellery offers a way for me to create smaller scale sculpture which allows my messages to be communicated to a wider and more varied audience in an inherently personal way (see also Figure 13).

During my travels around the world I am often stopped by people to compliment my talisman and they easily accept my interpretation of the cross without any aggression, suggesting that my design has achieved my goal.

Moscow Biennale

The theme for the Moscow biennale, 2015, was “how to gather”, key to which is how to communicate, how to find a common language, how to respect each other if we disagree – even if we are enemies. I exhibited Crucifixion (Figure 10, 11 and 12) in the biennale and it gave me the opportunity to explore on a larger scale my themes of both the body and the cross, creating abstractions of both. Crucifixion uses wood salvaged from historic sites (holding centuries of knowledge) to create the shell and internal space. The wood and space are pierced by glass nails which are both a symbol of aggression and a symbol of creation. They might also be viewed as symbols of home in that they hold things together. In the biennale exhibition it was placed with a mural using religious symbolism which was a collaborative work by a group of my students who came from different religious backgrounds and who had to navigate an understanding of each other and their perspectives to create the piece.

Ironically, as a sculptor, I am inherently adding another layer of narrative to the truth but I hope that the honesty of my narrative helps people to question more and delve more deeply into what the truth may be.